Here is a sprawling review I wrote in 2008 as an attempt to comment on dance (practices, issues, tendencies) in the Bay Area.

ALMOST EVERYTHING I’VE EVER WANTED TO SAY ABOUT BAY AREA DANCE BUT DIDN’T HAVE THE CHANCEKeith Hennessy responds to the 2008 WestWave Dance Festival

August 16-24, 2008

Produced by Dance Art, Dancers’ Group, YBCA

Dance Wave 1, 2, 3

The Novellus Theatre at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts

Equality. Free Speech. Democracy’s Body. The Bay Area. The West Wave Dance Festival. In the future everyone will have 15 minutes of fame. In the West Wave Dance Festival each choreographer had five minutes on the big stage at Yerba Buena. Three programs. Thirty-five companies. An equitable and representational form of democracy that celebrates a utopian correction to the cultural segregation of most of our daily lives. This kind of democracy is also championed by the Izzies (the Bay Area’s Isadora Duncan Dance Awards) and might even be considered a San Francisco or Bay Area ‘Value.’

Diversity is generally a white liberal idea. Multicultural ensembles, as well as arts spaces and festivals that offer multicultural programming, serve an audience that is primarily white, i.e., not diverse. This held true for this year’s West Wave festival. If diversity programming does not attract diverse audiences, what is its goal? What aspects of the West Wave festival were not compelling to local audiences? With each company having only five minutes on stage, the reason to attend was not to see a specific company but to be wrapped in a crazy quilt of found fabrics, to taste test from an international smorgasbord, to enjoy or be challenged by juxtapositions, comparisons, frictions, and resonances between companies. From this holistic or systems view the 2009 West Wave Festival was a delightful success. But if so few people want to experience this wide-angle portrait and if the blackouts between pieces symbolize cultural divides that no amount of stage sharing can bridge then should this form be repeated?

The intentional creation of multicultural ensembles (SF Mime Troupe, The Dance Brigade, ODC) has its roots in a radical critique of mainstream society’s institutional racism. These troupes emerged from 1960’s and 70’s counter-cultural contexts inspired by the radical left, lesbian-feminism, and a series of ruptures in the arts. During the turbulent 60’s the established powers that refused to defend Native American independence or Civil Rights were quick to fund Alvin Ailey as the #1 American cultural export. An image of African American inclusion contrasted the facts at ground level. Progressive and reactionary forces are continuously at play and depending on one’s perspective social justice is improving (Obama) or not (US schools, prisons). The white choreographers and audiences of the SF Ballet receive massive and disproportionate funding from both public and private sources. Simultaneously, there are people in several powerful positions in Bay Area arts funding and presenting who are deeply committed to equitable distribution of resources and increased visibility for minority and/or marginalized cultures.

A review written in the spirit of the West Wave Festival would give an equal amount of commentary to each company that performed. It might even give each group the same quality of praise and/or critique, interrupting any attempt to favor or privilege one performance over another. My response is more subjective, as evidenced already by a particular politicizing of perspective. I am a fan of postmodern strategies and critical of dance that seems either nostalgic or unquestioning of tradition.

There was a striking similarity to most of the 35 dances staged in the festival. Dancers entered in the dark. The lights came on to reveal dancers in a still shape. Dancers moved in time to music for somewhere between four minutes, thirty seconds and five minutes. And then, in an obvious relation to music or narrative, the dance ended with stillness (or a repeating movement), and a slow fade to black. The audience applauded.

Interruptions to this structure were infrequent enough to stand out as nearly daring even if they simply used other accepted choreographic tactics, like walking on in light (Smith/Wymore), beginning in the audience and then moving to the stage (Chris Black), or dancing as if there was no beginning or end (Amy Lewis).

I have been looking for a way to simply describe Bay Area or American dance that seems to ignore most of the innovations and experimentation of the past 50 years, since Anna Halprin and Cage/Cunningham through Judson, performance art, contact improvisation and even Sara Shelton Mann/Contraband. (Disclosure: I performed with Contraband from 85-94.) European dance writer Helmut Ploebst uses the awkward term “modernistic American post-post-modern” to contrast Bill T Jones, Stephen Petronio, and Neil Greenberg from their contemporaries in Europe including Meg Stuart, Jan Fabre, Jerome Bel, or Vera Montero. I think his term could also apply to several contemporary Bay Area companies including ODC, Deborah Slater, Stephen Pelton, Brittany Brown Ceres, Janice Garrett, and Leyya Tawil. But of course this kind of classification is mostly useless and unnecessarily divisive. Kathleen Hermesdorf’s group choreographies might fit this term but her duet work with musician Albert Matthias does not. Alex Kelty’s choreographic research projects interrupt many modernist notions but his dance for Axis shown in West Wave was an expressionist dance-theatre drama that could easily be classified as post-post-modern.

I apologize in advance to the 35 choreographers whose work I mention here. I use your creative labors to spark an eclectic critical commentary on tendencies in Bay Area contemporary dance (and beyond). Certain prejudices prevent me from experiencing your work as you intended. Seeing the performance and reading the program bios demonstrates each and every choreographer’s deep commitment to dance. From a deep well of dance-making experience I respect the deep commitment, personal vision, and years of hard work with inadequate resources that is embodied in each of the following dances.

Given the massive effort it takes to accomodate 35 companies sharing a single stage, each program ran remarkably smoothly, production values were high, and everyone looked great in lights designed by Michael Oesch. Congratulations to the producers, technicians, designers and dancers.

Dance Wave 2

Wednesday August 20, 7pmTo a striking song of acapella voice and clapping by Quay,

Alayna Stroud began the evening with a dance on and around a suspended vertical pole. Bold sharp arm gestures punctuated a dance of moody poses. With Quay singing of an inability to let go of the pain, the dance ended with Stroud, high on the pole, spinning, inverted, holding on.

An ex-SF Ballet dancer now award-winning international choreographer,

Robert Sund offered a trio ballet to Leonard Cohen songs. Leaping and spinning, Ryan Camou generated an energy that was not met by his partners-en-pointe, Robin Cornwell and Olivia Ramsay. The choreography and performance seemed more like an earnest study for young dancers than a finished work appropriate to this scale of venue.

Ankle-belled and brightly dressed in orange and green, seven dancers from the Odissi dance company

Guru Shradha performed a ritual dance of slowly spiraling arms in lovely light. The group formations, always frontal facing and symmetrical, seemed to freeze the action within the confines of the stage, rendering it a visual event to be viewed rather than a spiritual event to be felt.

A trio of women in white danced an impeccably synchronized choreography of glances and head gestures. Choreographed by

Wan-Chao Chang whose extensive cross-cultural training includes Balinese dance and music, There was like something that Ruth St. Denis dreamed of making but lacked the technical training to manifest. The work recalled a women’s Modern dance chorus from the 1920’s or 30’s updated with deeply embodied non-Western movement that could only be possible with the cultural migrations and fusions of the past thirty years.

Cynthia Adams and Ken James of

Fellow Travelers Performance Group choreographed an absurdist romp that satirized martini culture, an easy target. The central image was a dancer (super compelling Andrea Weber) attached at the back by a long wooden pole to an enormous wheel. It looked like it a design by Fritz Lang or Hugo Ball. As she muscled herself to spin, the wheel circled the stage while martini holding dancers ducked or swerved to avoid being knocked over. Dancers traded clothes, Ken ended up wearing a dress, and Cynthia crossed the stage with a vacuum. No one noticed the woman-machine that kept it all moving.

In this festival everyone gets five minutes. That’s one image, one gesture, one relationship, one moment within a twelve-scene event. In this context

Christy Funsch made a clear and subtle choice. Alternating curvy sensual gestures and sharp punctuating lines, Funsch slowly traversed the stage. The music, like the dancing, was emotional but not dramatic. Reading her body’s writing from audience left to right, I was drawn into the choreography, and therefore the body, and thus an intimate encounter.

The most memorable sense I have of

Deborah Slater’s

Gone in 5 was the joyful meeting of full-bodied dancing (big leg circles, tumbling off tables), bluegrass with a driving beat, and untamed red hair. A female trio in red wigs and black dresses seemed to enjoy every bit of their five minutes but I missed the conceptual/intellectual engagement that inspires most of Slater’s dance theatre. By this point in the program I wondered if the five-minute rule and the late summer scheduling encouraged a lite touch, or discouraged more serious inquiry.

Innovators of the American Tribal style of belly dance, Carolena Nericcio and

Fat Chance Belly Dance began with controlled undulations of arms, spine, pelvis, and belly. In super colorful costumes they gathered speed, energy, and volume, with finger cymbals rocking, into a final gesture of accelerated spinning, their skirts dancing like flames.

Amy Lewis’s Dada meets Judson happening was a delightful revelation. Titled and performed as a series of tasks, 35-40 performers filled the stage playing cards, wrapping gifts, stacking blocks, juggling, stuffing balloons in their clothes, and jumping rope. A trio of musicians played live. Two dancers in wheelchairs snaked through all the activities linking them like unraveling yarn. Someone read kid’s books. An actual kid did something else. Andrew Wass and Kelly Dalrymple, wearing their signature white shirts, red ties and black pants, repeatedly lifted each other from a chair at center stage. Others ran into the audience distributing free gifts. And that’s not all that happened! The stage came alive. The audience woke up. Reviewer Rachel Howard wanted to flee the theatre. People wanted to know what was going on. (What the heck was going on?!!) People wanted it to end. People wanted a gift. This is the piece that made it worthwhile for me to leave the house and risk my attention on dance. Thank you Amy.

Hip hop renaissance woman

Micaya served up a celebration of booty that recognized its own hype and played the hip hop game with a self-awareness that the suckers on MTV can’t conceive. The choreography flirted with the music’s butt-worshipping lyrics, as if the body (booty) could talk back, call and response. Her diverse young crew,

SoulForce, jumped through musical genres and even crumped to classical.

As soon as SoulForce arrived on stage, their friends (friends of hip hop) started calling out to the dancers in a kind of direct feedback that Rev. Cecil Williams referred to as “listening Black”. Dance styles are not the only ways that dance marks cultural difference. Audience response differs as well. Do we “listen Black” or “White”? Do we enter ritual spaces, times and trances or do we observe with fourth wall intact? And if we have a preferred style of response, is it appropriate to jump forms, or do we stay obedient and respectful of cultural norms? Some of us experience everything on the proscenium stage, from ballet to Afro-Peruvian, hip hop to performance art, as post-colonial and post-European. Are there any traditions that have escaped colonial conditioning? There is a difference between shared (diverse) and universal (we’re all the same). I wonder if by foregrounding the equitable sharing of space by diverse communities we exaggerate difference and emphasize borders, preventing the awareness of the universal fact that we all dance.

Kara Davis made one Tuesday afternoon… for a group of young ballet dancers from (I assume) the LINES ballet school. Eleven dancers moved from whole group movement to duets in which the dynamics of shared weight spoke to human connection and mutual influence. One falls and domino ripples of weight pass through the group. It’s easy to fall into the trap of treating young or student performers as the adults they want to become. Davis artfully avoids this trap by leading these ballet bodies into relaxed weight and playful encounters. As well the simple costumes of nearly monochrome brown street clothes helped a more innocent sensuality emerge. The minimalist bluegrass score by Gustavo Santaoalla well supported the piece.

Kumu Hula (hula teacher)

Káwika Alfiche and several of his students performed

A Goddess with live singing and drumming. The work began as a solo invocation within a circle of light. The fabulous costumes involved big full skirts and circles of what seemed to be dried grass or brush around their ankles, wrists and head. The headpieces were like organic halos, bursts of energy extending in all directions. The program notes inform that the dance tells a dramatic story of volcano goddess Pele’s youngest sister. The movement was mostly front facing and synchronized and I lacked experience to follow any gestural or energetic narrative. What I could sense was cultural pride through an attention to visual, sonic, and gestural craft.

In DanceWave 2 there were nearly as many people on stage (partly due to Amy Lewis’ cast) as there were in the audience (approx. 100). Why aren’t more audiences attracted to this programming? Is it so tough to convince friends or colleagues from particular (dance) communities to see you perform if you’re only on for five minutes and sharing the stage with eleven other companies that do not share the same music and dance culture? I think that if the tickets had been $5 or free with a request for donations, (instead of $25 with a $7 service charge), the producers could have doubled or tripled attendance with no loss in box office income. But that doesn’t answer the larger question about what compels people to attend or avoid contemporary dance performances in any style.

Dance Wave 3

Wednesday August 20, 9pmWorking in both San Francisco and European dance contexts causes some dissonance in my perception. In the Bay Area we accept overt religious practice in the form of folkloric songs and dances as a normal occurrence. In Europe this would be considered highly unusual, either ridiculed as naïve or witnessed from a non-believing distance. I have never experienced what we unfortunately call Ethnic Dance in a contemporary dance context in Europe unless the dance/music forms are in an experimental encounter with European forms, or the forms themselves are being questioned or deconstructed. Every time I refer to my work as ritual (and I do), a European brow gets wrinkled. Still I question the language of god and religion in our work, especially as we advance towards a presidential election in which every candidate feels compelled to end their speeches with an emphatic, “God bless America.”

Aguacero is a Bomba company directed by Shefali Shah. Focused on Afro Puerto Rican Bomba the company sincerely describes their work as connected to basic folk religion practices: healing, ancestor worship, embodying the natural world, and initiating youth in traditional practice. Their work is a syncretic encounter of West African cultures filtered through the Caribbean while reframing Spanish colonial dresses, shoes and language. At Dance Wave 3 they performed Hablando con Tambores a dynamic skirt waving dance that surfed the fast-paced, joyful wave created by three drummers and four vocalists. After a lively solo, a second woman came on stage in a competitive/collaborative face-off of tightly patterned skirt tossing, moving so quickly that my eye memory retained traces of circling and spiraling fabric.

Like her Ballet Afsaneh colleague Wan-Chao Chang (DanceWave 2),

Tara Catherine Pandeya has cross-trained in several non-Western dance forms and traditions. In a dance of circling hands and micro percussive movements of shoulders and head, Pandeya danced in a sensual world evoked by the music played live by the trio Marajakhan. The traditional Uyghur music and the long braids attached to Pandeya’s hat recalled the work of Ilkolm Theater (Uzbekistan) who performed the gorgeous epic Dance of the Pomegranates at Yerba Buena earlier this year. Both performances evolve from diasporic Central Asian Turkic cultures.

Alex Ketley in collaboration with Rodney Bell and Sonsherée Giles of

Axis Dance Company created a tense and intimate dance drama. Punctuated by quick gestures and sudden conflict the lovers seemed caught between intense attraction and secret fears. The dancers’ intimacy with each other’s bodies further demonstrated the struggle of any two people to connect. In this case the two people had to cross the divide between man and woman, as well as between a person who walks on feet and legs and another who travels by wheelchair. When Bell fell backwards to the floor, supported by Giles, we realized that he was fully strapped to his chair and could now crawl like a snail with house attached until he muscled his way upright. The piece ended the way it began and why not? Most couple encounters circle through familiar territory.

Brittany Brown Ceres choreographed

Shade a quintet of women bound in a space defined by a rectangle of light. The work alternated synchronized and solo movement with a variety of lifts to a score of uninspired contemporary techno. An unfair question blocks my vision. “Why are they dancing like that, working so hard with such tired vocabulary and choreographic assumptions?” This question only reveals my inarticulate frustration. Also it seems too specific about dance ceres (whose work I’ve never seen before) when in fact I ask it all the time when seeing post postmodern Bay Area dance. In the program text Ceres tells us that Shade was “crafted in public spaces to study landscapes which are designed to substitute for psychological balance and to unlock descriptive communication made of movement instead of words.” The gap between their craft and my experience was overwhelming.

The strangest work in the West Wave Fest was

Brooke Broussard’s

Moving The Dark. A solitary figure in black unitard, complete with hood, moved continuously in rhythmic patterns of extended sweeping limbs and undulating spine. In some contexts this costume and this action would cause uproarious laughter but here it was only weird, as in otherworldly. Three lengths of blue carpet were unrolled to mark the space into a geometry of lines and triangles but the choreography seemed to ignore these differentiated spaces, so after a couple of minutes I did the same. Six other dancers in three pairs completed the cast of this surreal-psychological modern ballet. Blackout. We clap. Then we hear a loud scream.

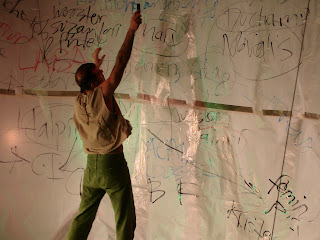

A woman’s voice is heard from the balcony. Some pop song I can’t name. “I’m gonna make a change in my life.” Then singing erupts throughout the well-lit house. The singing, by choreographer

Chris Black and company, was charming as if we caught these citizens singing along with headphones on a rural trail or alone in their apartment. Moving towards the stage one of the performers faces the audience from the front row and sings only the first half of U2’s “And I still haven’t found (what I’m looking for).” A repeating motif of “change” of course recalls Obama but it is only afterwards that I find out that the piece is entitled

Headlines and includes found gestures from print media with a fractured medley of pop music. Musical encounters between the performers grew increasingly complex, mashing one song against another, or everyone briefly singing the same song. Counting aloud, Michael Jackson’s Man in the Mirror, and little dances of borrowed shapes in absurdly out of context scenarios, became a virtuosic arrangement and performance of everyday life. The emotional power of this piece was a surprise. What seemed like a formal intervention and a cute referencing of pop culture became an impassioned cry for renewed meaning and solidarity. Wow.

Tango Con*Fusion offered a round robin of tango duets danced by an ensemble of six women betraying (they call it bending) the gender roles of traditional tango. Bay Area values have evolved to a point where bending gender and queering tradition is neither radical nor compelling. The dancing seemed polite, lacking the intimacy and tension that tango often evokes. I was reminded of Terry Sendgraff’s aerial dance company in the 80’s embodying a (lesbian) aesthetic that avoided competition and celebrated equal partnership. You might need to check your punk rock at the door to be able to enter the best of these egalitarian worlds.

Through Another Lens by

Sue Li Jue is a modern ballet that confronts the legacy of the Vietnam War within a body that is both American and Vietnamese. The sound score succeeded in blending two distinct voices: a blues text by an American vet underscored by traditional Vietnamese folk music. Soloist Nahn Ho is a strong dancer whose spiral falls, clear shapes, and sudden turn to the audience dared us to witness him, a young man pushed to the limit by the political tensions that he embodies.

Second generation South Indian dancer and choreographer

Rasika Kumar crafted the festival’s most overtly political piece.

Gandhari’s Lament represented the story of the blind mother of 100 sons who were all killed in the Great War of the Mahabharata. With ankle bells marking every percussive step, Kumar’s powerful dancing used both abstract and mimetic movement to communicate a mother’s grief. Her bitter, closing curse could as easily be directed at today’s murderers.

Zooz Dance Company’s

En Route opened with a gorgeous solo by Jessica Swanson in a backless top that highlighted her amazingly articulate back and hips. The fusion dancing of Zooz, co-choreographed by Jessica McKee, features ensemble Middle Eastern dance that is super precise and seductive. Their skirts, especially the boa-like trim, did not meet the quality of the dancing.

If an internal voice demanding “Why? Why?” prevents me from seeing most Modern dance made by contemporary choreographers, the volume elevates to near screaming when I’m watching modern ballet.

Liss Fain’s Looking, Looking was another of the festival pieces that seemed like a study for young ballet students. How did these works get curated over the sixty choreographers who got turned down? Was there a category for student works? Or did these pieces represent the best of the ballet applications? In Fain’s work two men and five women in sexy black shorty shorts danced for five minutes to Bartok’s dramatic Concerto for Viola. There were lifts and arabesques; the dancing was neither stupid nor compelling.

Dance Wave 1

Thursday August 21, 9pmCharlotte Moraga restaged and performed an original composition by Kathak icon Pandit Chitresh Das. The dance basically manifested its title, Auspicious Invocation. With liquid wrists, crystalline forms and an open expressive face, Moraga began in a circle of light, dancing her invocation to the four corners. Properly concluding the ritual, she ends with a bow. Moraga is an excellent dancer who has been immersed in this form for 17 years.

But what does it mean to wear a sari or Indian costume on stage in San Francisco? What relevance or resonance does a contemporary audience appreciate when watching traditional ritual dances? What combination of training and inspiration might result in a local Akram Khan? Someone who masters Kathak and subjects it to contemporary and global questions of performance? Someone who no longer feels responsible to represent a nostalgic or idealized cultural representation? Similarly what social context might encourage an African American dancer in the Bay Area to dare the kind of genre-busting performance of Faustin Linyekula? Someone whose expression of African-ness is dependent neither on folkloric tradition (pre or post slavery) nor on the specifics of urban Black cultures? I wonder what might happen if some of the local ‘ethnic’ companies abandoned representational music, costumes, and static ritual forms. I have been inspired by the complicated revelations of Khan, Linyekula, and other companies directed by non-Western artists traversing the borders of genre, ethnicity and culture, reframing ritual and spectacle for today.

Recent Bay Area resident

Erika Tsimbrovsky crafted an evocative teaser of visual dance theatre that suggested we keep an eye towards further projects. Paper gowns that ballooned around the dancers as they dropped suddenly and a scratchy recording of a slow turning music box evolved a performance language sourced in image and memory. The dancers hid inside the dream space of their skirts, and two of them birthed themselves naked as the lights faded.

Sheldon B. Smith and Lisa Wymore made a smart, hip little dance generated from YouTube. Imitation, lip-synching, and multiplying the action via ensemble movement heightened our attention to the found sources and challenged a reconsideration of live performance’s relationship to online videos. What does it mean when highly trained dancers are viewed by an audience of 100 or 200 when non-professionals can be viewed by 3 million? Not only is YouTube a bigger performance archive than we could ever have imagined, but nearly all of YouTube’s most viewed videos involve dance or bodies in performance. Too many of the Dance Wave artists entered in the dark and held a static pose as the lights came up, so it was an unintentional and pleasant intervention to have the Smith/Wymore quartet walk onto the stage with the lights on.

In

Mary Sano’s

Dance of the Flower a woman’s head floats above a massive parachute skirt, under which we assume many dancers are hidden. To Bach’s cello the skirt begins to breath. I’m in a retro shock. Really retro. I’m thinking Duncan, perhaps after Fuller. This is neither an innovative skirt dance like Fuller’s nor a well-researched prop piece that recalls Mummenschanz or Momix. It’s more like a children’s theatre game evolved from metaphoric, expressive early Modern dance. Emerging from the skirt we are presented with a lovely poem of skipping women in Duncan-style, Greek-inspired tunics. (How many companies in this festival are all-women?) Sano, a third-generation Isadora Duncan dancer, choreographs under the influence of a series of assumptions about nature, women, dance, bodies, and flowing fabric without any recognition of the nearly 100 years of challenging and rewriting those assumptions.

Most Bay Area dancers work with such a poverty of resources (money, space, time, scheduling, management) that it is a marvel that there were nearly 100 companies applying to be in this festival. Nonetheless the lack of engagement and risk with visual design, especially light and sets, is often disappointing. This is as true for the last ODC concert that I attended as it is for most of these five-minute wonders.

Dandelion’s

Oust (excerpts) began with an odd solo backlit by an upstage performer with a handheld instrument, while a woman at a microphone laughed. The light shifts to another dancer who writhes, falls, twitches and freezes. Unfortunately this is neither Eric Kuyper’s strongest work with the company nor a great example of why we ought to experiment with light. But Kuyper continues to intervene with tradition, challenge conventional assumptions, and craft risky interdisciplinary experiments.

Smuin Company resident choreographer

Amy Seiwert created Air a ballet pas de deux featuring Jay Goodlett and Tricia Sundeck. These dancers have considerable professional experience compared to the ballet dancers in Programs 2 and 3 which made this dance all the more disappointing with its lack of risk and insistence on neoclassical vocabulary and stale gender roles. The crowd was loud and vocal with praise. SF Chron reviewer Rachel Howard thought it was the best of the fest. I’m sure that Goodlett is a fabulous dancer but at Trannyshack, SF’s legendary drag club, he would be referred to as a ‘man prop’ (the male as functional object in service of the “female”). In diva culture this is not necessarily an insult.

Charya Burt’s

Blue Roses reimagines Laura from The Glass Menagerie as a Khmer princess trapped in her own world. Wearing traditional Cambodian clothes Burt knelt in a circle of light, her wrists held at a sharp 90 degrees, palms pushing out, her fingers reaching well beyond their physical length. Despite the specific cultural invocation of gesture, costume, music and light projection Burt avoided mimetic acting in favor of detailed and articulate physical expression. Her intense presence and sensitivity were so palpable that even the subtlest of wrist and head movements seemed to charge the space around her. Similar to the slow intensity of early Butoh or Deborah Hay’s cellular movement the audience could either be bored to sleep or provoked into a radical encounter with the present, presence. I was impressed, touched.

Nine bodies in white, on their backs, marking the diagonal. In waves of canon the dancers of

Loose Change pulse into and up from the floor. Choreographer

Eric Fenn’s vocabulary reveals itself slowly in fragmented reference to break dance, hip hop and more. Percussion-based group movement proves this crew is the strongest large ensemble of the festival. Invoking a future city of dance monks the team falls into place remaking the opening image.

Another transition between companies. Another attempt at discreet set up in soft blue light followed by a black out, followed by lights up on dancers in stillness. Would it hurt to reveal the action, skipping the blackout and the precious stillness? Does the stage have to remain this nostalgic place of magic? How did the dancers get there? I don’t know they just appeared in gorgeous light and then started dancing.

I’m curious to see more work by

Limbinal a young collective of artists directed by Leonie Gauthier. For their five minutes they presented

INside which featured two man/woman duets, one on a table, accompanied by live cello. The work on the table, the mutual lifting, and the increasingly dramatic cello suggested a meeting of Scott Wells and Sara Shelton Mann in a chamber ballet.

Women lifting men ought to be more common in 2008 but its only other occurrence in this festival was with Wass & Dalrymple in

How many presents… Contact Improvisation began in 1972 with an intention to democratize (remove the hierarchies from) the duet. But this is only one of the aspects of the postmodern dance ruptures that seem generally absent in Bay Area contemporary dance.

Luis Valverde (choreographer) and Eleana Coll gave a rousing presentation of Peruvian Andean dance. She, fabulosa in pink satin and white ruffles. He, dapper in blue suit, black boots, woven belt and wide brimmed white hat. Hankies revealed in their right hands, they begin to court each other. Indigenous footwork in colonial drag, they dance a timeless seduction of approaches, smiles, spins, and retreats. Their steps are rhythmic and light. The music alternates between symphonic and a military snare. These are handsome people and we want them to get together. When their faces pause almost touching, almost kissing, I want to cheer. The steps increase to skips but she never loses her coy cool. Now the hips are marking time more than the feet. A big energetic finale, racing against the music and they freeze, together. Big applause.

A voiceover instructs us to turn on our cell phones and invites us to document the dance. On stage are two men and one bride. The audience starts snapping pics. And thus begins Snap a work by Jenny McAllister for

Huckaby McAllister Dance. A long tulle train attached to one man, when pulled, drags three pink dressed ladies onto the stage. The voice clowns our habit-obsessions with phones and the documentation of every waking moment. “Keep the truth safe from time. Isn’t that beautiful?” For a while this is physical comedy via ensemble dancing. Then the voice talks about grandparents in Minsk and the only photo in which no one smiled. “Bubby says it was just like that.” With efficient craft the weight of history is invoked and the simple social satire becomes only a preparation for a more intimate touch to occur.

Somei Yoshino Taiko Ensemble closed the evening with a fusion performance in which the dancers were the musicians, and the dance was an enactment and embellishment of the musical score. Four drummer/dancers moved around and within a circle of large and small drums. Sharp strikes from one arm. Boom! The other arm shoots vertically to the sky, extending its line with drumstick in hand. Quick shift. Boom! The energy ebbs and flows in a continual flirting of yin and yang carrying marked by stark freezes and silences. Synchronized activity amplifies the sound in such a concrete way: more drummers, more force, more sound. The pace increases towards a quick finale. The final gesture’s silence is the loudest action of it all. And they drop, disappearing into the center of the drums.

In a film clip shown at the Nijinsky Awards in Monaco a French interviewer asks, “WHAT IS dance to you, Mr. Balanchine?" The response was, "just dance."